Soon, that world is upended: The Germans march into Paris and refugees flee south, overrunning Viann’s land. She returns to tending her small farm, Le Jardin, in the Loire Valley, teaching at the local school and coping with daughter Sophie’s adolescent rebellion. Cut to spring, 1940: Viann has said goodbye to husband Antoine, who's off to hold the Maginot line against invading Germans. This trajectory is interrupted when she receives an invitation to return to France to attend a ceremony honoring passeurs: people who aided the escape of others during the war. In 1995, an elderly unnamed widow is moving into an Oregon nursing home on the urging of her controlling son, Julien, a surgeon. Hannah’s new novel is an homage to the extraordinary courage and endurance of Frenchwomen during World War II. Waters has found a superb metaphor for the love that dares not speak its name, and developed it with remarkable ingenuity and power: another stunning performance by a young writer whose promise seems just about unlimited. And the long denouement, in which Margaret, having risked everything, awaits the fulfillment of Selina's promise that stone walls do not a prison make (“You need only want me, and I will come”), grates exquisitely on the reader's nerves, right up to its brilliant climax-in the revelatory image of a “mud-brown gown. Waters has researched her mood-drenched Victorian gothic quite impressively (down to such convincing minutiae as this injunction to search all prison visitors: “Infants may be taught to pass on blades, in their very kisses”). The developing closeness between the two women-intensified by evidence that Selina is telepathically sending ‘tokens’ of her affection to Margaret's home-is juxtaposed with flashback scenes that gradually disclose the truth about Selina's supposed powers (especially as embodied in the visitant she claims is her collaborator, seductive “Peter Quick”-in a knowing nod to Henry James's The Turn of the Screw). At Millbank, Margaret is drawn to the vibrant figure of Selina Dawes, a “spirit medium” blamed for the death of a client during a séance. This is intended as therapy, for Margaret has recently attempted suicide-an act presumed to stem from the recent death of her father (a respected Renaissance scholar), but is in fact connected to a disappointment in love. The dominant “world” is London's Millbank Women's Prison, to which highborn Margaret Prior comes in 1874, as a “Lady Visitor” offering solace and companionship to Millbank's wretched inhabitants.

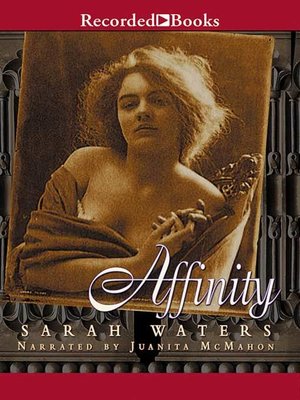

This ambitious second novel, a richly detailed exploration of the mysterious ‘affinity’ that appears to unite two lonely women, boldly extends the range of the British writer ( Tipping the Velvet, 1999).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)